Apr

2023

Why is Everyone Talking About Decodables? (Part 1 of 3)

Have you noticed an uptick in the use of the word ‘decodables’ recently – whether in the media, your professional learning, or in the teachers’ lounge? You’re in good company! Decodables (also called Phonics Readers, controlled texts, basal readers, or primer readers) are enjoying somewhat of a renaissance in education, due largely to the prevalence of new research on how the brain learns to read and what this means for best practice in literacy instruction.

This topic is going to be covered across 3 blog posts. In the first post, I want to review the features and purpose of decodable texts, discuss why we’re hearing so much about them in media and research these days, and explain why they are such an important tool that we need to incorporate into our instruction. In the second post, I will discuss how you (and your team) can make a game plan for reviewing and selecting the best decodables to use in your classroom or add to your shared building resources. In the third post, I will share my insights about a few different decodable products that I’ve recently reviewed, and hopefully give you some ideas to make some thoughtful purchases.

Depending on how many years you’ve lived on this planet, or how many years you’ve been in education, I’m willing to bet you’ve had experience with decodables in the past. Perhaps you’ve read (or at least heard of) ‘Dick and Jane’ books like the sample below.

What are some words that come to mind when you think about decodables? For myself as an early reader, I categorized them as boring, contrived, nonsense, fake or ‘practice’ books. The words used were overused (“Why is every book about a cat? I don’t even like cats.”) or of low-utility to me (How often do you have the chance to use words like ‘hex’ or ‘jut’ as a 7-year-old?). I did not find them engaging, and I was much more interested in getting my hands on a colorful picture book. I know there are many attitudes and experiences that readers can have with decodable books, which can also elicit a positive sense of comfort and pride for emerging readers. Equally, classroom teachers can also have a wide range of attitudes, experience, and perceived value in using decodable texts in their instruction. For myriad reasons, decodables have taken a backseat in classroom instruction over the past several decades, and were no longer considered a standard resource.

The impact of Science of Reading Research

These past few years, the phrase “Science of Reading” has worked its way into every aspect of education from professional learning (I’m personally taking a “Science of Reading” book study seminar with my local Cooperative Educational Service Agency), and university course offerings (I’ve had to update and realign several syllabi and course objectives to align with new research) and resources (“Buy this Science of Reading aligned product!”) to movies (“The Truth about Reading”) and podcasts (“Sold a Story”), Facebook groups, and everything in between. I have friends who don’t have children or aren’t even in the field of education reaching out to ask me what I know and what I think about SoR. In short… unless you live in a remote village without wifi access, you’ve been punched in the face with the Science of Reading topic.

What the Science of Reading refers to is this new body of research about how the brain learns to read – it taps into findings from linguistics, cognitive and educational neuroscience, and educational psychology. It is not a program or a method or an agenda – it’s simply a body of knowledge that is engaging the field of education to reexamine what we believe and how we teach reading. It has drastically shifted our focus to the importance of systematic and sequential phonics instruction for early and emergent readers, from Kindergarten through about 2nd grade (and likely beyond).

In my tenure as an educator, I have seen the focus on emerging and early reading as primarily focused on using engaging, authentic books, language and conversation, and modeling reading strategies in a Workshop Model. The goal is to get books in student’s hands and to help them see themselves as successful, confident, skilled readers that can think about, talk about, and enjoy reading. And to that end, we’ve been using tools like highly engaging trade books with patterns ( “See the ___. See the ___.”) and teaching students to use initial sounds and picture clues (“Hmm.. it starts with /f/ and it’s green. What could it be? Yes, a frog!”) to help them get up and running with books and persevere past tricky parts. We teach students to automatically recognize the most useful “Snap Words” or High Frequency Words (“the” “and” “what”…) that they are likely to encounter in their books. As we learn letter sounds, we guide students in noticing the first letter and identifying the sound it makes to “get your mouth ready” to say the word. We model and guide their practice with strategies like previewing a text, making connections, asking questions, and retelling. (It should be noted that new research has shown us that using strategies like “Sammy Skip It” and come back to it, and over reliance on picture clues, is actually a harmful habit to teach students and should be avoided in reading instruction).

You might be thinking, “That all sounds great, but what about phonics instruction? Didn’t you just say that new research tells us it’s like… super important?” Yes! Children HAVE been getting phonics instruction all along. Reading, Writing, and Phonics study are a tripod – three legs that are balanced and hold up Effective Literacy. I still strongly support the workshop model as described above, and I believe the ultimate goal of reading IS to get students talking about and loving great books that challenge and excite them. I ALSO understand and agree with the movement to incorporate more deliberate, systematic, and sequential phonics instruction into literacy. Through workshop, students are introduced to phonics patterns that are then deliberately reinforced during Reading and Writing blocks.

In order to get the most leverage out of our phonics skill practice, we need students to linger in the transition between phonics and reading where they can apply what they’ve learned with controlled texts (decodable books) and encoding practice (phoneme grapheme mapping, spelling) of that same skill. This rehearsal or sheltered practice must happen BEFORE they are able to be successful with any other kind of book (authentic, trade, or leveled book). The goal of reading engaging authentic texts has not changed, but the path must become reinforced with more deliberate phonics practice.

Features of Decodables

What are some features of controlled texts or decodables? How are they different from other kinds of books? There are three categories of words that readers encounter in a decodable, ranked in order or prevalence: 1) phonetically regular words that are able to be sounded out based on phonics skills that have been taught (ex: CVC words, final e words…) 2) high frequency words (HFW) or sight words that have irregular patterns (ex: what, you) 3) story or content words (ex: chair, bicycle). You’ll see a lot of different opinions on the ratio or percentage of the categories of words in a book, but all researchers agree that the majority should be from category 1: phonetically predictable words that follow the focus pattern. This gives students the maximized opportunity for practicing the target skill.

It seems reasonable to expect that a decodable series would follow a clearly defined scope and sequence of phonics features – typically this means starting with short CVC words with short vowel sounds (cat, tin, mop) and progressing to digraphs (ch, th, sh) and so on. Each book should focus on only one target phonics skill. Many series are cumulative, meaning any previously learned phonics feature is fair game in all subsequent books. These books are intentionally designed to promote phonics mastery, and are intended to be used for a limited time during structure lessons.

By now, it should be pretty clear why decodables are a MUST for emerging and early literacy instruction.

- They offer students extended practice and application with a phonics skill.

- They discourage students from developing habits such as guessing based on pictures or context.

- They follow a systematic progression that is mutually reinforced by the reading and writing curriculum.

- They hold students and teachers accountable for for transferring and practicing phonics skills in a structured, supportive context.

- They are an critical rehearsal step on the road to fluent reading of authentic texts.

- They build student confidence and self-efficacy and enjoyment of reading.

Incorporating Decodables into the Curriculum

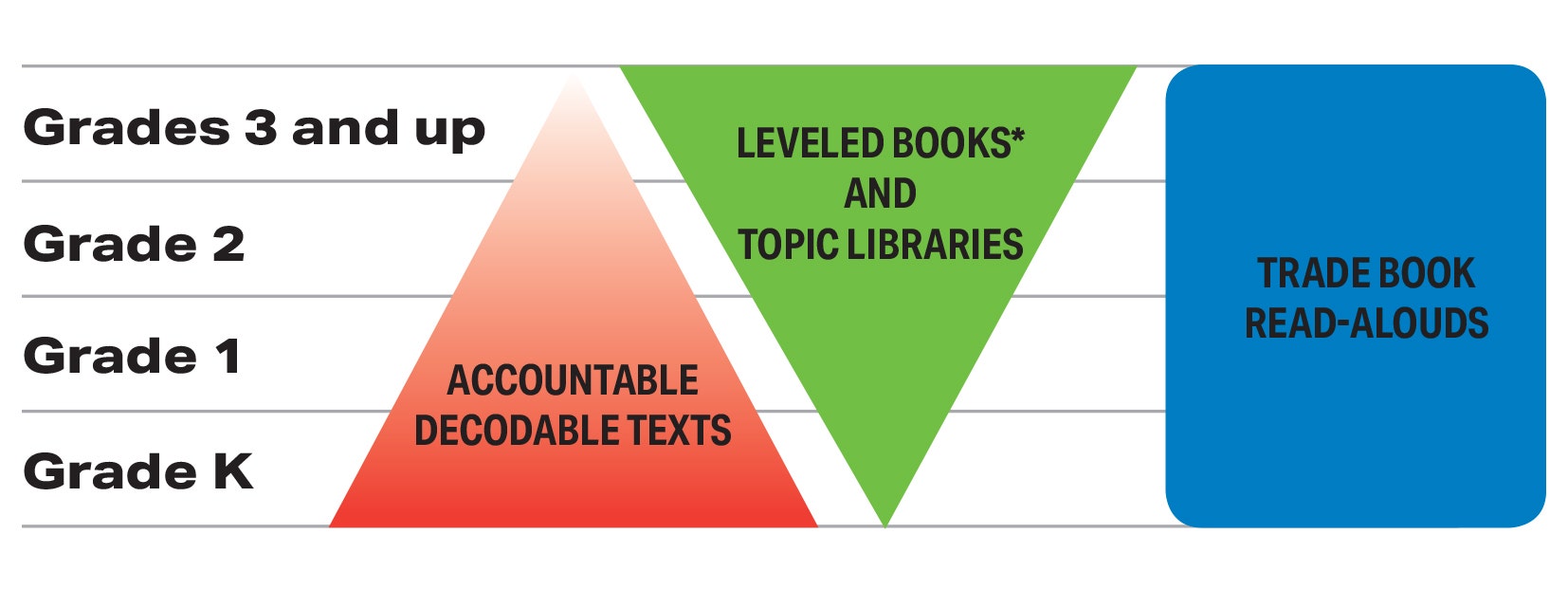

For what grade levels are decodables helpful and appropriate? Most decodable books or systems will say they are designed for universal instruction in Kindergarten and 1st grade classrooms, at a minimum. Some extend to 2nd grade. Outside of universal instruction, they can also be used to support small group or Tier 2 / 3 interventions for higher grades, as long as the content is developmentally appropriate (not too babyish and won’t cause emotional harm). I really appreciate this image from Wiley Blevins that shows us how decodable texts are most critical in the early grades and phase out as students are more independent and successful with transferring their skills to authentic leveled texts. And all along, we see the importance of trade book read alouds at every grade level. We must always be reading high quality, rigorous grade level material to our students to model and instruct with reading strategies, provide language and thinking practice, and develop cognitive and executive functioning skills agnostic of phonics mastery.

I’m in! Now what?

I’m sure we can all agree that decodables have a primed and welcomed space in our classrooms. And yet, there’s a very real reason why they quietly seemed to disappear from our consciousness over the past several decades. They were of such poor quality, and nobody liked them! I was gifted some really old phonics readers for my own children at home, and I hated them so much that I tossed them. I thought – if I’m going to snuggle and read to my little children at night, at least I want to read them something we can enjoy and discuss. I was clearly very misinformed, and I wasn’t playing the long game of having support materials at home when my children started school. I also don’t blame myself, because they were really, really boring and stilted and… weird.

What you might love to learn, as I did, is that decodables have come a long way in recent years. Publishers are paying attention to the demand and churning out some very high quality readers that you are going to enjoy. In my next blog post, I’ll get into the nitty gritty of what makes a “good” decodable, and how to make selections that will suit your needs.

–> On to Part 2: Choosing Decodables

Citations:

Burkins, J. M., & Yates, K. (2022). Shifting the balance: 6 ways to bring the science of reading into the balanced literacy classroom. Hawker Brownlow Education.

Jen and Wendy. (2022, October 7). 5 problems with using MSV (aka the Three-cueing system). Informed Literacy. Retrieved April 20, 2023, from https://informedliteracy.com/five-problems-with-using-msv/

The Science of Reading. Benchmark Education Company – Building Literacy and Language for Life. (n.d.). Retrieved April 20, 2023, from https://www.benchmarkeducation.com/knowledge-hub/the-science-of-reading

![]()